“For I was hungry and you gave me something

to eat, I was in prison and you came to visit me.”

A simple meal can nourish both the body and the soul.

Food sustains life, but shared meals foster dignity, warmth, and belonging. When we feed the hungry, we don’t just fill empty stomachs – we recognise the person before us, affirming their worth and reminding them that they are not forgotten.

In every loaf broken and every meal offered, we imitate Christ, who not only fed multitudes but also shared His table with those in need of love and redemption.

Mercy can’t be confined to walls or boundaries. It reaches beyond circumstances, beyond past mistakes, and beyond society’s labels. Visiting the prisoner – whether someone behind bars or someone trapped in fear, shame, or loneliness – is an act of liberation. It is a reminder that no one is beyond God’s love. A conversation, a listening ear, or simply showing up can be a source of hope, breaking the chains of isolation and offering a path toward healing.

When we share our blessings with the hungry and visit those imprisoned – whether physically or emotionally – we become instruments of God’s mercy. We bring nourishment where there is emptiness, freedom where there is confinement, and healing where there is brokenness. True mercy feeds not only the body but also the heart, restoring the dignity of every person we encounter.

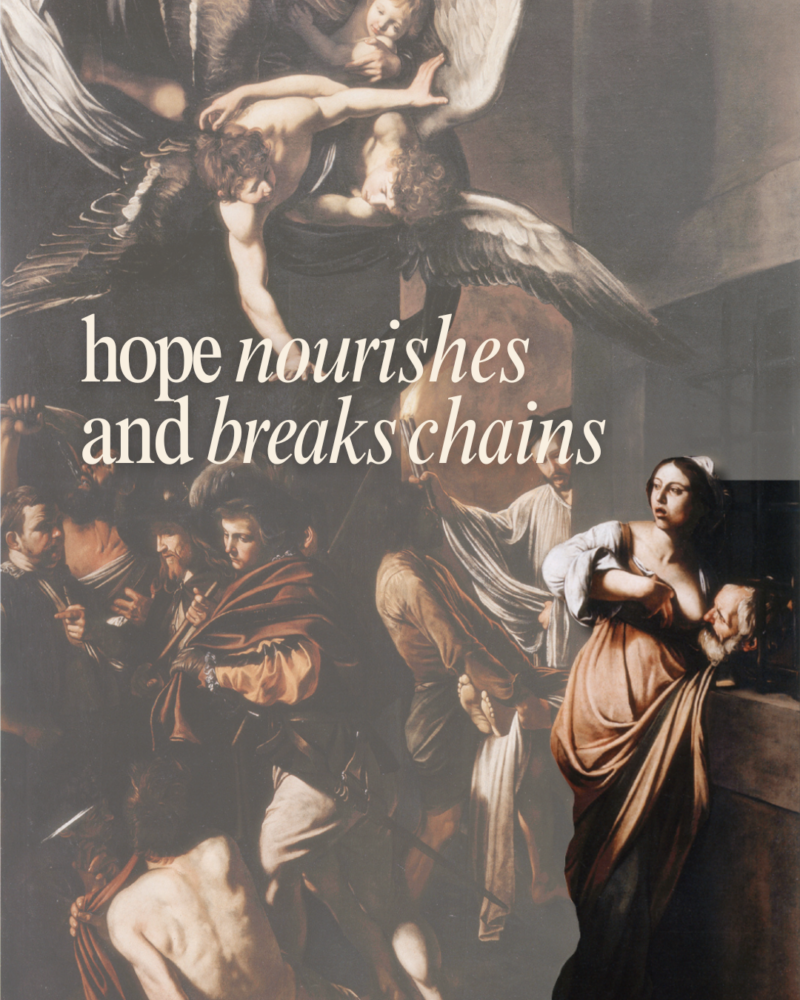

Art Insight