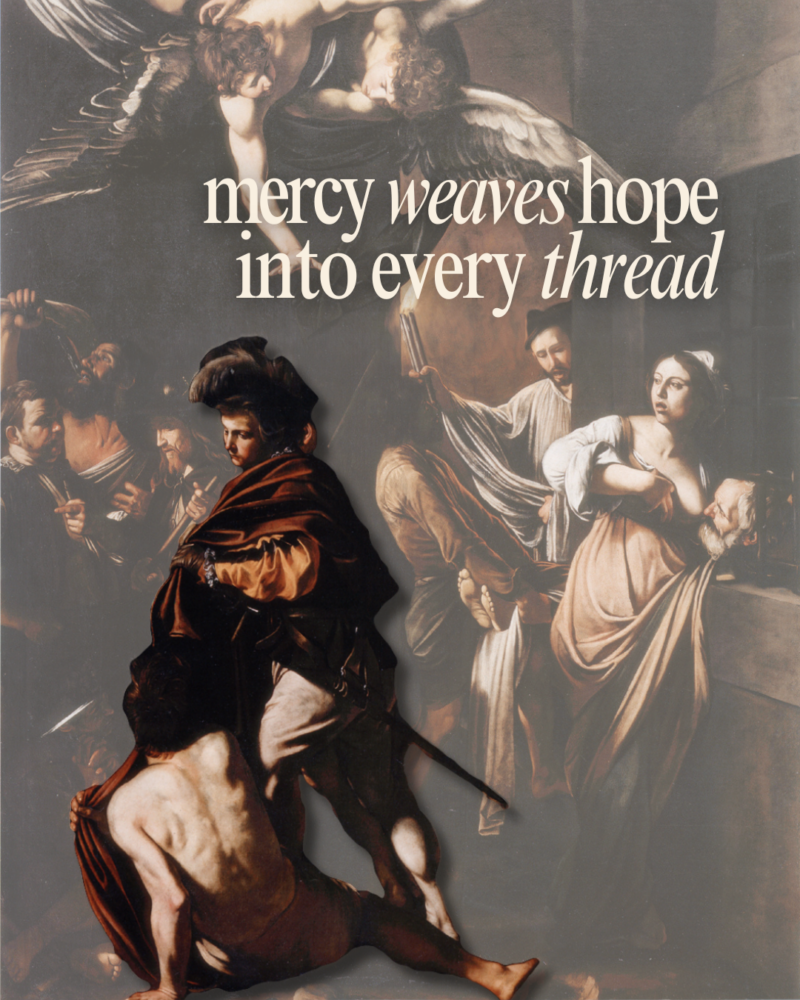

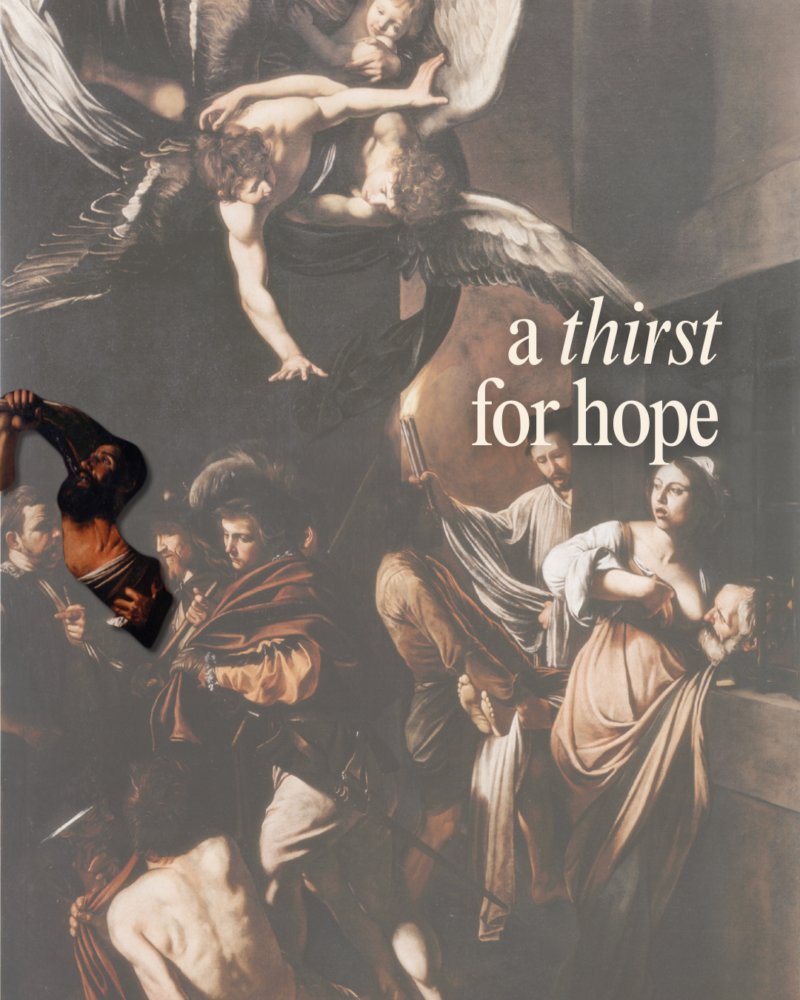

“ I was naked and you gave me clothing.”

Mercy begins when we notice another’s need and act to fulfil it. To clothe the naked is not just about providing garments; it is about restoring dignity, warmth, and a sense of worth to those who have been stripped – physically or emotionally – of what they need to thrive. Clothing shields us from the elements, but it also represents protection, care, and belonging.

Many in our world lack adequate clothing, whether due to poverty, displacement, or misfortune. But beyond material need, others feel exposed in different ways – vulnerable to judgment, shame, or rejection. Mercy calls us to cover not just bodies but also wounds of the heart. We can clothe others with compassion, understanding, and respect, ensuring that no one feels forgotten or unworthy.

Every act of kindness that restores dignity – offering a warm coat, supporting someone in rebuilding their life, or simply treating another with love – reflects the mercy of God. Just as He wraps us in His grace, we are called to clothe others in mercy, ensuring that no one stands exposed to the coldness of indifference.

Art Insight